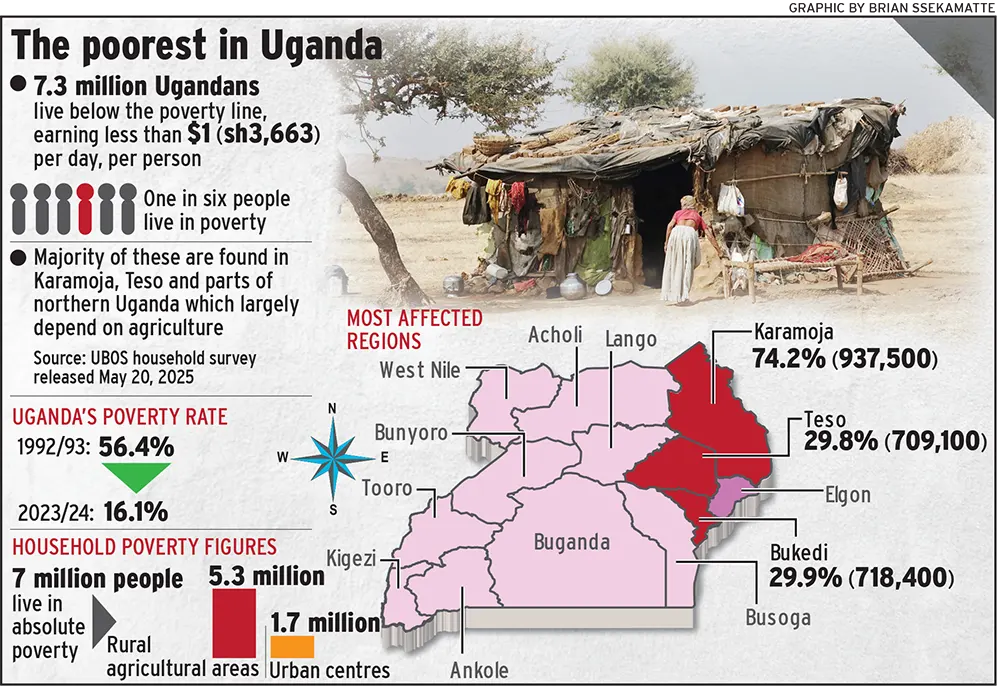

Despite being the backbone of Uganda’s economy and a source of livelihood for over 65% of the population, farming regions paradoxically have some of the country’s poorest communities, according to the 2023/24 National Household Survey. In a four-part series, Joshua Kato investigates the reasons why certain regions remain impoverished despite having rich natural resources. This first instalment focuses on cattle keeping and poultry rearing.

In the distance, Mt Moroto dominates the receding daylight skyline. Below the slopes of the mountain, a herdsman, Peter Lokeris, ‘talks’ to his cows as he guides them to a kraal.

“The life of the Karimojong depends on animals. If their animals die, they will also die!” Lokeris says.

According to the National Livestock Survey, livestock rearing (cattle, goats and chickens) is the backbone of Karamoja, as 98% of the population depends on it. Lokeris’ herd has over 100 cows.

By Karamoja’s standards, his family is rich. However, the value of his herd is low compared to a similar one, for example, in Kyankwanzi district in western Uganda. Keeping cattle traditionally According to statistics from the 2021 Livestock Census and the agriculture ministry, there are 3.3 million hybrid/exotic cows in Uganda.

About 1.1 million and 1.35 million exotic cows are in the western and central regions, respectively. These regions produce about 80% of the milk consumed in Uganda.

Other areas include Elgon, with 50% of their herd being exotic, Toro, Bunyoro and Kigezi, which average 24%. Meanwhile, Karamoja has the highest concentration of indigenous cattle compared to other areas.

Kotido has nearly 700,000 head of cattle, Kaabong has over 500,000 and Moroto has around 450,000.

Some households in Karamoja have as many as 500 head of cattle, but this does not translate into improving incomes in the region, with 85% of the region’s population living below the poverty line.

In contrast, in Ankole or Buganda, with 500 head of cattle, that household would be ranked among the richest in the area.

The average cost of a cow in Ngoma, Nakaseke district, is sh1.2m. This means that a person with 500 head of cattle has sh600m on the farm.

And yet in Karamoja, cows are part of the family.

“They do not see livestock farming as a business, and they only sell cows that they do not like,” cattle keeper Lokeris says.

However, Karamoja can pick a leaf from the cattle-keeping transition in western and central Uganda. “We need to create a cluster of model farms in Acholi, Karamoja and Teso regions,” Dr Tonny Kidega, a dairy farmer in Gulu, says.

Kidega has tried to spread the gospel of modern dairy farming across northern Uganda for the last 10 years. Exotic cows in Karamoja?

“Given the extreme hotness and lack of resources, [exotic breeds] are not the cows for Karamoja,” Dr Ben Kezeron Ogang, a former livestock programme officer for the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, says.

He adds that hybrids are heavy feeders and drinkers, which means that they cannot survive in the absence of grass and water.

Dr Bernard Ojore, a veterinary officer in Soroti, says beyond the low[1]quality livestock, even uptake of veterinary services is very low.

“Because these animals are hardy, farmers think they do not require the regular services of veterinary officers. Yet, we have knowledge that can help increase the herds’ productivity,” he notes.

The Government and other stakeholders are seeking possibilities of turning the ordinary cow in Karamoja into a money-minting one.

Chicken rearing When it comes to poultry, according to the livestock census, the country has an estimated 57 million birds, with around 17.5 million exotic.

Busoga and Teso have some of the highest numbers of indigenous breeds, while the central region boasts over 80% of the exotic flock.

Nearly all chicken farms with over 50,000 chickens are located in the central region, at least one in Kamuli, Busoga, but none beyond that.

In Teso, Karamoja and Busoga regions, almost every homestead has chickens.

However, the earnings are paltry since these birds are kept under free-range systems.

“Some of the chickens do not have shelters. They spend the night in trees in the compound,” says Christine Apolot, in Olilim trading centre in Katakwi.

What she does is what almost every other poultry farmer does: No vaccination and no supplementary feeds at all.

However, Dr Richard Lumu, a technician at the indigenous chicken breeding centre, MUZATDI, Mukono, says indigenous chicken can bekept commercially for profits.

Traditionally, chickens are housed in temporary structures and, in some cases, spend the night with other livestock or in a room that is not used by the farmer’s family at night, such as the kitchen.

Lumu explains that there is no protection from predators. With this traditional system, there is no flock management, but the farmer sells chicken when he needs to.

Though the costs are very minimal in this system, there is no way to measure profitability.

“A solution to these issues is to keep the local chicken, using modern poultry farming methods,” Lumu says.

This system can easily be adopted in Teso, Karamoja and Busoga areas with the largest flock of indigenous chicken.

Mini m u m effort myth Even where some farmers in Teso, Karamoja or Busoga keep improved breeds, they put in half the effort compared to farmers in the central region and the west.

“We have tried to act as model farmers for the rest. Some have picked lessons, but the majority stick to the traditional ways,” says Teddy Wabomba Wanzunula, a 2016 Best Farmers Competition winner running a farm near Soroti town.

She says even many of those who adopted better practices do not apply them consistently, leading to losses. And yet, with poultry, lucrative as it is, there are no miracles.

“The profit margin in poultry is so thin that the moment you do not take care of it well, you will find yourself operating at a loss,” Robert Sserwanga, a farmer and farming consultant, observes.

“They want the layers to produce at 98%, but are feeding them at 50% or even 40%. This is expecting a miracle. They want broilers to gain 2kg after eight weeks, but they are feeding them just a quarter of the required feed,” Sserwanga says.

At the end of the day, the chickens will produce nothing, and start taking even the little money that the farmer has. This “give little but expect much” behaviour cuts across entire agricultural systems. It is one of the reasons farmers remain poor.

Transformation

Years ago, when high milk-producing cows were introduced to Uganda, adopting them was a big challenge.

Most farmers in cattle-keeping areas of western and southern Buganda loved the traditional, long-horned cattle.

“Farmers were scared of losing their heritage. They see this long-horned cow as a heritage,” observes Dr Apollo Ataho, one of the directors of Frank Family Estates, a modern livestock farm in Sembabule district.

But then, these cows that took five to six years to mature had low commercial value because they produced very little milk — about half a litre a day — and little beef.

This meant poverty for the population. However, 30 years ago, mass adoption of the hybrids started, especially in the Ankole sub-region and parts of Sembabule district.

Because of this, poverty levels in western Uganda have dropped to 8.7% in 2023/24 from 56% in 1992. This is largely because the population earns a living from livestock.

Next week, poor seeds and blessed with water, but no irrigation.